Gustav Vichy, French Automaton: “The Waltzing Couple”

Gustav Vichy

French Automaton: “The Waltzing Couple”

c.1870

Mixed Media

Nicholas and Shelley Schorsch Collection

Essay by Kaitlyn Roberts

Automatons are traditionally viewed as mechanical wonders derived from the minds of engineers. The animation of the human form is considered their most intriguing aspect. During the time of their production, automatons were viewed less for their mechanical ingenuity but rather for the spectacle that was created by the mimetic atmosphere they created. Today, modern toys use electric motors and batteries to function, but the mechanical principles behind the production of such toys has changed little . Two examples of automatons made by Gustave Vichy and Zinner and Sohne are the works in our exhibition.

An atmosphere of wealth often surrounded automatons as they were frequently displayed to charm guests. Culture and location also played a large role in the significance of the automaton. In the late 18th-century and early 19th-century Europe was emerging from both the Enlightenment and the Industrial Revolution, creating a cross-pollination of modern mechanical and classical philosophical ideas. Europeans were moved by a desire to understand the meaning of life and representation of the human form.

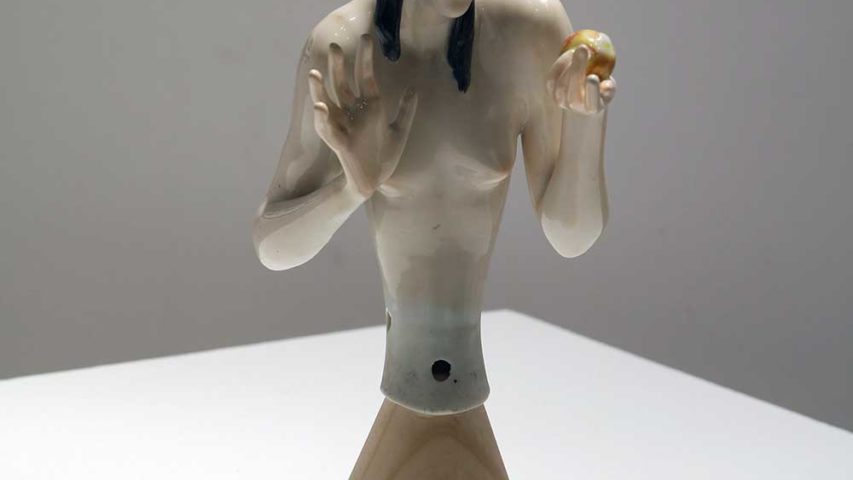

Late 19th-century France was home to diverse artistic views. The Frenchmen Gustave Vichy, born in 1839, grew up in his father’s store which sold mechanical toys. After his father’s bankruptcy Vichy, at the age of twenty-three, decided to create his own factory creating automatons with an intended focus on the production of musical automatons. His wife Maria, whom he married in 1864, sewed fashionable clothing for his dolls. Vichy was the first automaton manufacturer who, in his small factory, oversaw every step of the production process. Vichy’s automatons were always heavy sources for mixed media. In his 1870 Waltzing Couple he combines glass, silk, metal, bisque porcelain, and mohair. Vichy’s Waltzing Couple was inspired by the 1850 dancing dolls originally made by Theroude. The work features a couple embraced in each other’s arms in preparation for a dance. Once the key under the woman’s skirt is turned they traverse the floor in a large square-rotation while twirling around one another.

In comparison, Germany in the late 19th-century was marked by war and treaties that led to a culmination of diverse influences and the birth of German Realism. Founded in 1845, Zinner and Sohne, a company based in Schalkau Germany, produced cheap commodified toys but specialized in quality machines. The company created many automatons but little is known about the logistics of the company itself. Zinner and Sohne’s 1890 Clown Drummer and Performing Poodles is a playful piece featuring a young boy in a silk suit and a matching velvet jacket with a drum and drumsticks in hand, accompanied by two poodles off to his right. Upon winding the crank the boy’s hands beat the drum while the larger dog to the far right activates a string that triggers the jumping apparatus attached to the smaller dog in between them. Zinner and Sohne made automatons in many mediums, creating an elaborate scene for the human forms to be placed upon. These German automatons are widely collected because of their playful music and their amusing motions.

The lively nature of automatons could capture the imagination of anyone at any age. The appealingly animated human form led to the current day culture surrounding dolls. With the influx in production of toys came a rise in mechanical ingenuity. Both Gustave Vichy’s and Zinner and Sohne’s automatons are prime examples of wonder.

Bibliography

Carriker, Kitti. Created in Our Image: The Miniature Body of the Doll as Subject and Object. Bethlehem, PA.: Lehigh University Press, 1998.

Kang, Minsoo. Sublime Dreams of Living Machines : The Automaton in the European Imagination. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2011.

Liu, Catherine. Copying Machines: Taking Notes for the Automaton. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.