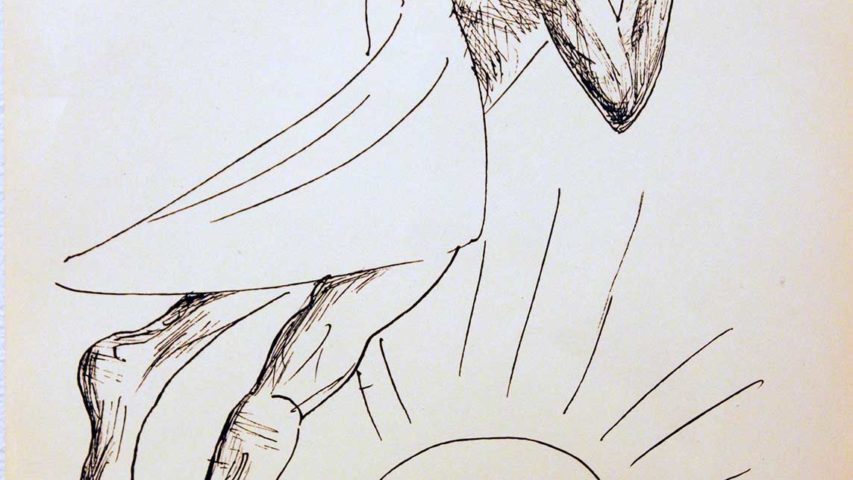

Keith Haring, Flying Man

Keith Haring

Flying Man

1975

Offset lithograph

Private collection

Essay by Kaela Kennedy

Keith Haring was an emblematic figure of the New York art scene in the 1980s. His iconography was ubiquitous and his characteristic figures pervaded everything from advertising campaigns to subway graffiti. Two of Haring’s pieces appear in this exhibit. Both images are connected by subject matter, showing depictions of winged, angel-like men. The first, a print entitled Flying Man, is an offset lithograph work on paper. It measures sixteen inches by twelve inches. This image shows the graphic black outline of a winged human figure surrounded by bright pink zigzag lines radiating outwards from the body. The print reflects Haring’s stylized treatment of the human figure. The androgynous figure is largely defined by two continuous lines that form the legs, torso, arms, and head. Its wings are suggested by two lines extending from the neck and head of the figure and intercepting the legs. Both the lines of the figure and the pink radiating lines maintain the same weight throughout the piece creating a sense of uniformity.

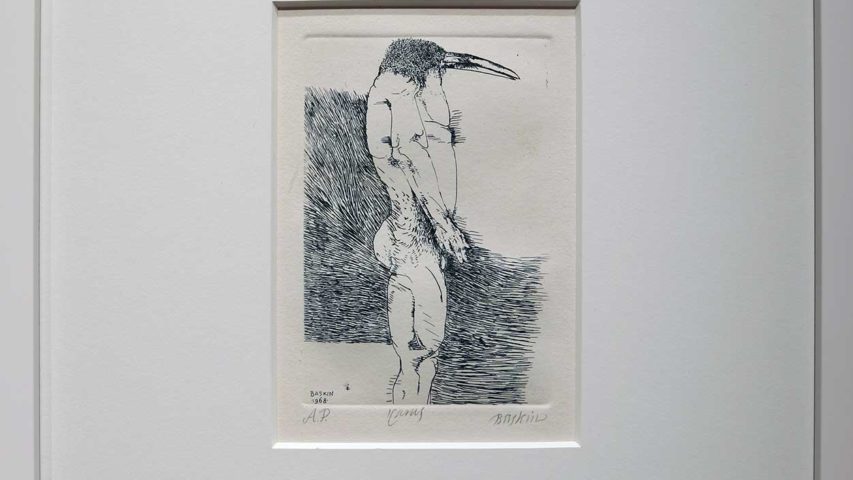

The second work is a window from a New York City MBA subway car that has been tagged by both Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat around 1980. The window is 24 inches wide by ten inches tall, and about half an inch deep. This found object is transformed by the two symbols inscribed in black ink that can be attributed to Haring and Basquiat. On the right side of the plane, Basquiat’s tag is inscribed. His typical three-pronged crown is drawn in a single continuous line, creating a unified shape. On the left we see an iteration of Haring’s winged man. Here, the figure’s upper body suggests that the winged man has hands, unlike that of the lithograph. Another variant is a large X-shape on the chest of the winged man and six short black lines emanating from its head.

Haring’s work was likely influenced by his own fervent Christianity, manipulating typical angel iconography into androgynous, genderless winged figures. Haring’s work, though complex in iconographic language, is never arbitrary. By digging into Haring’s symbolism, it is possible to see that these two figures serve as commentary on the corrupt nature of modern culture. The winged figure in the lithograph is distinguished by the pink lines radiating from the body itself.

In other examples of Haring’s work, the same lines serve as symbols of nuclear radiation; the artist had a noted fear of nuclear holocaust, which manifests itself in many of his works. Here, the nuclear energy corrupts the figure. The figure drawn on the subway window is in a different way corrupted; he bears a hollow “x” on his chest, which Haring used as a symbol of damnation. This contradicts the ‘holy’ lines emanating from the angel’s head, which typically refer to purity and holiness in Haring’s work. This dichotomy illustrates a conflict of nature, similar to the fall of the winged Icarus.

Bibliography

“Bio.” The Keith Haring Foundation. Accessed March 23, 2017.

http://www.haring.com/!/about-haring/bio.

Haring, Keith, Ralph Melcher, and Götz Adriani. Keith Haring: Heaven and Hell.

Ostifildern, Germany: Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2002.

Haring, Keith, Robert Farris Thompson, and Shepard Fairey. Keith Haring: Journals. London:

Penguin, 2010.

“Keith Haring: The Political Line Symbols.” de Young Museum. February 04, 2015. Accessed

March 23, 2017. https://deyoung.famsf.org/keith-haring-political-line-symbols.

Phillips, Natalie E. “The Radiant (Christ) Child.” American Art 21, no. 3 (2007): 54-73.